bachelor of arts ’42, master of fine arts ‘48

Nature, stone lithography, elemental to Nelson Sandgren’s art

Grab the rain jacket, wool hat, and a stack of 150-pound watercolor paper, full sheets clipped to plywood. Toss the sawed-off card table into the van on top of the old backpack filled with tubes of watercolor and a palette or two, balsa sticks and plastic egg trays full of moist pigments. Add brushes, of course, and a sleeping bag just in case the weather’s really good for it, hoping the seas are still big and the foam is swirling around the headlands. Work in patches of rich color dug out of the plastic egg cartons with a bristle brush. A few water spots won’t spoil the painting—they merely certify it was done on site, in the hurly burly of weather and a feeling of utter freedom. Thus Nelson Sandgren kept alive his feeling for untrammeled nature, a sensibility never lost by the Chicago boy who came west in the Great Depression.

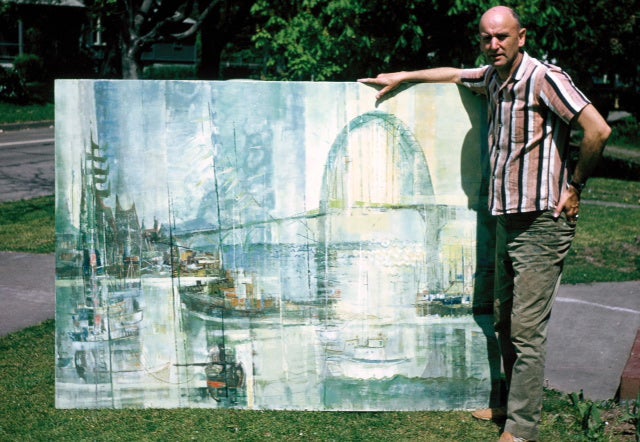

Above: Nelson Sandgren in 1962.

Sandgren exhibited widely around the Pacific Northwest. His oils, acrylics, drawings, woodcuts and lithographs are in many collections. In his many workshops and teaching career at Oregon State University, Sandgren consistently preached what he practiced—not a “look” but a discipline. He encouraged the development of observational skills and the need for constant work. He advocated the primacy of fluid drawing as a means to convey one’s individual observations and to explore the visual structures to convey them, returning the focus on nature as the root of self-discovery, avoiding mere cleverness, decoration, and the cycles of artistic fashion.

In 1940 Sandgren transferred from Linfield College to UO, to play baseball. As war loomed, UO art professors Andrew Vincent and David McCosh set the pace as landscape painters and as teachers, embodying an admirable lifestyle of painting, academia, and international travel. McCosh contributed a special emphasis on integrating observations of nature with pictorial structure, color ideas, and drawing. He provided Sandgren’s first exposure to the medium of stone lithography and for mural painting on a large scale. Jack Wilkinson concurrently impressed Sandgren and his contemporaries with the need for clear and logical visual organization and a strong intellectual component to the artists’ worldview. Sandgren met Maude Kerns, who introduced so many to the threads of modernism.

During World War II, Sandgren did basic infantry training at Fort Benning, Georgia, then served as a lieutenant at various posts stateside and in the Philippines before returning to UO for graduate work in painting. The MFA program involved him with familiar faculty and a host of architecture students who, like Sandgren, were back in school on the GI Bill.

After his MFA, Sandgren and his wife, Olive, went to Morelia, Michoacan, for a year of post-graduate work, collaborating there at the university with recognized Mexican painter Alfredo Zalce. Sandgren also played pitcher for Los Camineros, a local semi-pro baseball team. He and Olive travelled with the team to parts of Mexico seldom visited by foreigners. These experiences colored his conversation and study of Spanish for the rest of his life. The couple returned to the United States in 1949 with indelible memories of old Mexico, a mental store of images, and a lifelong study of Spanish.

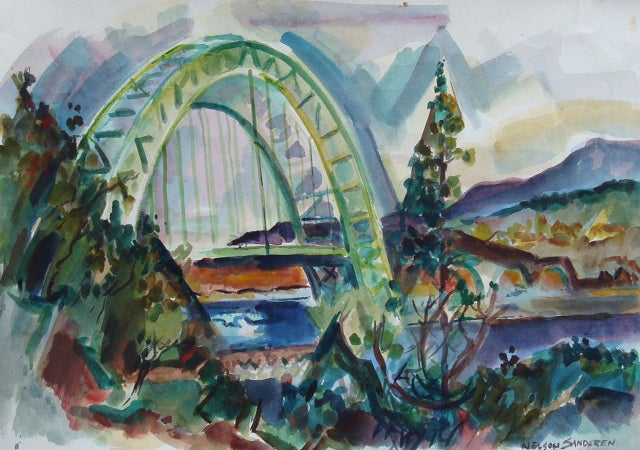

Above: Yaquina Bay Bridge, watercolor, 22”X 30," by Nelson Sandgren.

Vincent and McCosh recommended Sandgren for a teaching position at Oregon State College in Corvallis, where he was to teach for the next thirty-eight years. These were punctuated by a year of leave back to Mexico in 1950-51 and five sabbatical years of travel and painting in Europe. On the first of these sabbaticals, in 1959-60, he met up in southern Spain with Andrew Vincent. Sabbaticals to Europe were generally characterized by painting and study for six months in southern Spain, then six months of travel around Western Europe by train and car.

With the unfailing encouragement of Oregon State College Art Department Chairman Gordon Gilkey, MFA ‘36, Sandgren continued stone lithography, at first in the litho crayon direct drawing technique he had been taught by McCosh. In the early 1960s he obtained an old cast iron Fuchs and Lang lithographic press and large litho stones for his own studio. Picking up, in a sense, where McCosh left off, Sandgren continued to extend his technical grasp into the demands of tusche washes and multiple color runs. His imagery concurrently developed further into pure landscape, portrait, abstract, and multifigured imaginative realms.

In addition to the Sandgren Coast PaintOut and Workshop event still organized annually by Sandgren’s son, Erik, Nelson Sandgren taught summer workshops every year around the state. For special lithography courses at Southwestern Oregon Community College and Central Oregon Community College, he disassembled his cast iron litho press and reassembled it on site. He brought all the required litho stones to whichever campus wanted the weekly Oregon State extension classes taught at night year-round. These classes and excursions created a web of friends to drop in on, paint with, or go out to coffee with—friendships and associations going back to those early days as a painting student at UO.

Above: Sandgren and his son, Erik, on scaffolding during the work on the airport mural in Eugene in 1989.

Recognizing Sandgren‘s capacity to work at scale, Eugene attorney and McCosh aficionado Roger Saydack helped match Sandgren’s talents and energy to a large portion of the Mahlon Sweet Airport mural project. Sandgren’s son Erik Sandgren, Carol Yates, and artist Mark Clarke (MFA ‘65) assisted Sandgren on the scaffolding in executing the largest mural in the Pacific Northwest: 4,000 square feet of wall-painted in situ during the summer of 1989. Below the undulating glue-lam beams is a synthesis of landscape and pictorial structure that represents an inheritance from McCosh's large Depression-era murals for the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C.

These indelible experiences left Sandgren and his wife with a lifelong fondness for the UO and for the role of higher education in general. Sandgren‘s mission as a teacher was informed by a trajectory set in Eugene and arcing high and far into the field of art. It was his feeling for this that lead him back to teach for the UO Board of Visitors and as visiting faculty for a year in 1986-87 after his retirement from Oregon State University.

Nelson regarded this return to UO as a capstone to his teaching career. In his notes for assignments and problems for young painters, one discerns the influences of Wilkinson, Vincent, and McCosh. Their vitally different approaches were synthesized by Sandgren in the crucible of his own work and teaching and effectively transmitted to generations of art students.

Along with the myriad students influenced by his teaching over the years, Sandgren’s vital interest in the landscape extends through the work of his children. Both have embraced key principles embodied uniquely by their father and take them forward as underlying concepts. Jan Sandgren (BLA ‘94) has contributed influential landscape projects for Los Angeles County. Her award winning designs are persuasive and functional real-world spaces. Erik Sandgren (BA, Yale and MFA, Cornell), artist and teacher, responds as a painter and printmaker primarily to mythic aspects of the Northwest landscape.

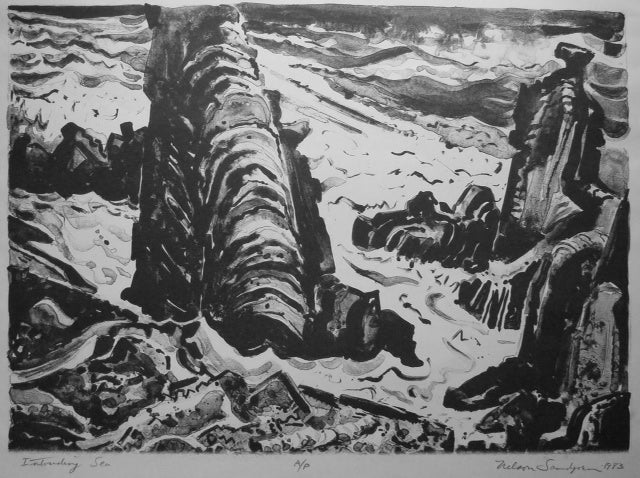

Above: Intruding Sea, lithograph, approximately 20” X 24," by Nelson Sandgren.

Sandgren, who died in 2006, felt himself to be part of a long tradition of artists and art history. Much of this sensibility emerged at the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts. His own influence as artist and instructor continues to be felt; his imaginative responses to nature continue to inspire.

The Hallie Ford Museum at Willamette University has planned a midsize retrospective of Sandgren’s work in 2016. In association with that exhibition and extending what it represents of Sandgren’s work in many media (cinematography, lithography, painting, and drawing) will be a monograph by Roger Hull, art history emeritus of Willamette University. This project joins a series that will place Sandgren’s work on the stage of Northwest painting in general by documenting its development, milieu, context, and influences.

Above: Cummins Creek, watercolor, 22” X 30," by Nelson Sandgren.

Above: Mahlon Sweet Airport mural segment, by Nelson Sandgren.

This story was published as part of the 100 Stories collection, compiled to celebrate our 2014 centennial and recognize the achievements and contributions of our alumni worldwide. View the entire 100 Stories archive on the College of Design website.