Art Professor Carla Bengtson's 'Learning Lizard' hiker's bandana

It takes a village to create a multidisciplinary and immersive art exhibition such as Every Word Was Once an Animal, a project led by Art Professor Carla Bengtson that was inspired by the gestural language of Western fence lizards. From rock mirror sculptures and animal-inspired music compositions to lizard semiotics and a perfume based on lizard pheromones, the exhibition merges art, science, dance, music, and olfaction to challenge the mind-body and human-animal divide.

Every Word Was Once an Animal, an exhibition years in the making, was originally set to run March 7 through July 26, with public performances, at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. The exhibition dates have been extended through Nov. 29, however, due to COVID-19, the museum is currently closed. A video tour and an extensive exhibition guide are on the museum website. Bengtson expects the exhibition will travel to other venues in 2020 and 2021.

“The origin story, like most of my projects, began with my biologist husband, UO biology professor Peter Wetherwax, sharing something he knew I would find interesting,” Bengtson recalls, laughing. “I’ve long been interested in animal cognition and overlapping sensory worlds. He pointed out a paper about how Western fence lizards use movement patterns to communicate.”

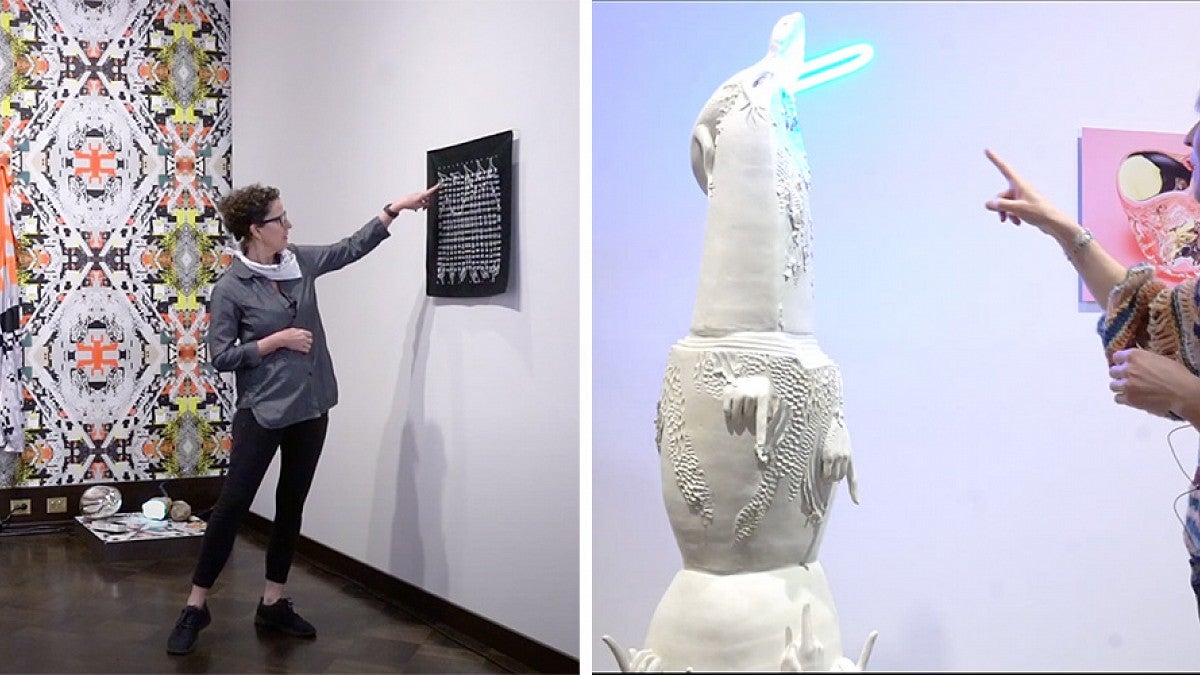

Bengtson in a JSMA gallery with 'Learning Lizard'; Art Instructor Jessie Rose Vala in a JSMA gallery with her sculpture 'Transmission'

Bengtson reached out to one of the co-authors of the journal article (“The Territorial Behavior of the Western Fence Lizard, Sceloporus occidentalis”), Emilia Martins, a professor of biology at Arizona State University and former professor of biology at the UO. Martins shared her research on how lizards communicate using scent and gesture to claim territory, express their individual identity, and attract a mate. Martins became a collaborator on the project, even contributing lizard robots used to communicate with lizards in the field.

“We should not take other creatures for granted,” Bengtson said. “The lizard—it’s such an unlikely creature to imagine having such a rich communicative world.”

Bengtson went on to study natural perfumery with Bay Area perfumer Jessica Hannah and created a perfume based on the fence lizard’s primary scent compounds which, surprisingly, include jasmonates, a common ingredient in perfume, as well as pyrizines, which are found in citrus, coffee, chocolate, and white wine. The perfume is shared in public events, along with tastings of the related compounds in sauvignon blanc and jasmine, grapefruit, and coffee-flavored chocolate truffles.

Bengtson also worked with local glass blower Sky Cooper to make a custom perfume bottle for the scent, titled “Sceloporus,” which was named a 2019 finalist for the International Sadakichi Award for Experimental Work with Scent by The Institute of Art and Olfaction.

The art professor also created the piece “Learning Lizard,” a “hiker’s bandana for learning lizard language that playfully pairs the gestural language of lizards with that of a human gestural language, American Sign Language.”

As the scope of the exhibition grew, Bengtson brought additional collaborators besides Martins, including choreographer Darion Smith, composer Juliet Palmer, and art alumna and Department of Art Instructor Jessie Rose Vala (MFA, ’15).

Smith and Palmer created a 45-minute interactive performance based on the lizard’s nonverbal communication, as well as “Rock Duet,” a site document video filmed by Vala of Smith and Palmer’s music with rocks at the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Blue River, Oregon. Vala also created stoneware sculptures for the exhibition and planned public tasting and olfactory events.

The group, minus Martins, spent 10 days at the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest for an artist residency.

Bengtson interacting with a lizard; the exhibition group at H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest

“We did a lot of site-responsive improvisational sound and dance there,” Bengtson said.

Bengtson hopes the exhibition prompts audiences to rethink the human-animal divide, a concept made popular by 20th-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who used the lizard’s lack of language to illustrate the basic difference between humans and animals.

“I would like exhibition visitors to take away an awareness that we are not the only species with rich cultural and social lives and complex forms of communication, and to become more fully aware of how differing sensory apparatus, temporo-spatial frames of reference, and culture intersect to make us unique.”