What began forty years ago as a makeshift photo gallery in a space the size of a freight elevator is celebrating its fortieth anniversary with a formal exhibition of 120 works at the Portland Art Museum through January.

“When we started it, longevity was just not an issue. It was not something that we thought about,” says Craig Hickman, one of the five cofounders of Portland’s Blue Sky Gallery and now a professor in the Department of Art at UO. “I don’t think anybody felt that his or her career trajectory was dependent on Blue Sky always existing.”

Yet not only does the gallery still exist, it has also gained an international reputation for significant exhibitions. The Portland Art Museum show, Blue Sky: The Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts at 40, honors the gallery not only for four decades of groundbreaking exhibitions but also for its achievements in helping galvanize public acceptance of photography as bona fide art.

Above: A banner hanging outside the Portland Art Museum announces the Blue Sky retrospective.

“Blue Sky at 40 is a celebration of an amazing nonprofit institution where people could look at original photographs at a time when photographs were still not quite accepted as a fine art,” Julia Dolan, the Portland Art Museum’s photography curator, says in a video about the exhibition. “The gallery [has] somehow managed to survive as this small, scrappy nonprofit for four decades.”

The Portland Art Museum show, a major survey of more than 120 works from Blue Sky over the years, runs through January 11, 2015. The exhibition, and an accompanying full-color catalog, “demonstrate the gallery’s meaningful contribution to an international dialogue about the meaning of photography in modern society,” the museum’s website states.

Presented chronologically, the exhibit illustrates how Blue Sky Gallery has helped viewers comprehend changes in the medium of photography.

“It’s really important for people to be able to see how … subject matter in photography has changed over time, and to see what kind of vision Blue Sky began with and then over time developed and refined,” Dolan says. “When they see the depth and the breadth of the work that appears in the exhibition, I think they will finally be able to understand just what Blue Sky has done for this community in the past forty years.”

Blue Sky began when a few young photographers decided to hang their photos on the walls of an unused room in a weavers’ cooperative. “It will be harmless. I’m sure that nobody’s around to complain about it,” cofounder Ann Hughes remarked at the time. “That was the germ,” cofounder Robert Di Franco says in an interview of the founders for Blue Sky: The Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts at 40, published by the Portland Art Museum to accompany the show. “And I swear, within a week’s time, the idea of hanging our own work exploded into this full-fledged idea of having a gallery. It was almost immediate. It was unbelievable.”

Frugality was fundamental to the plan, Hickman notes. “In the early years the five of us paid some of the expenses, mostly from unemployment checks. We also had a donations jar. Later we received some National Endowment for the Arts funding and other grant funding. The main strategy was, however, to keep costs low. We never assumed that we could spend a lot of money or borrow because something would come along to save us.” Adds Di Franco, “We paid twenty dollars a month for the darkroom and forty dollars for the gallery.”

With five cofounders—Di Franco, Hickman, Hughes, Chris Rauschenberg, and Terry Toedtemeier—the gallery was open five days a week, with each of the five gallery-sitting for five hours. As for what went up on the walls, the five founders all weighed in.

“At that time, we could sit around and decide what we wanted to show, and if there was somebody who was well known, some work we saw and liked, we just asked them to show, and they would say yes. You just can’t do that anymore,” Hickman says. “The precarious nature of photography, the way it was positioned in the art world, really worked to our advantage.”

The original gallery space “was tiny, like the size of a freight elevator, with burlap that we’d stapled to the particleboard walls ourselves,” Rauschenberg says. The group mailed posters from their shows around the country, and before long the gallery was “actually better known outside of Portland than in Portland,” Di Franco says.

Above: An early exterior photo of the original Lovejoy Street location. All photographs courtesy Professor Craig Hickman.

Forty years later, although the location has changed (and the gallery now owns its space), the shows are still decided by consensus, although the exhibition committee now includes members along with founders. “The committee is run in such an unusual way, but it has a nice honesty about it,” Hickman says. “The structure is democratic, but it works. To a certain extent, the work shown has always reflected the spirit of the time but also has been eclectic. It’s kind of like magic that it works the way it does, but I also hope that it changes over time, too, that it can adapt and not always be the same. “

The gallery has been nothing if not adaptable. Writer John Motley put it this way in an October 23 review of the art museum show for The Oregonian: “The creation of Blue Sky also coincided with a historic shift for the medium, and the work showcases its evolution from film to digital as well as from second-class discipline to respected art form.”

Motley notes that Hickman and his cofounders “maintained a purposefully eclectic program in [the gallery’s] first decade,” offering visitors a look at work ranging from daguerreotypes to new work by emerging artists.

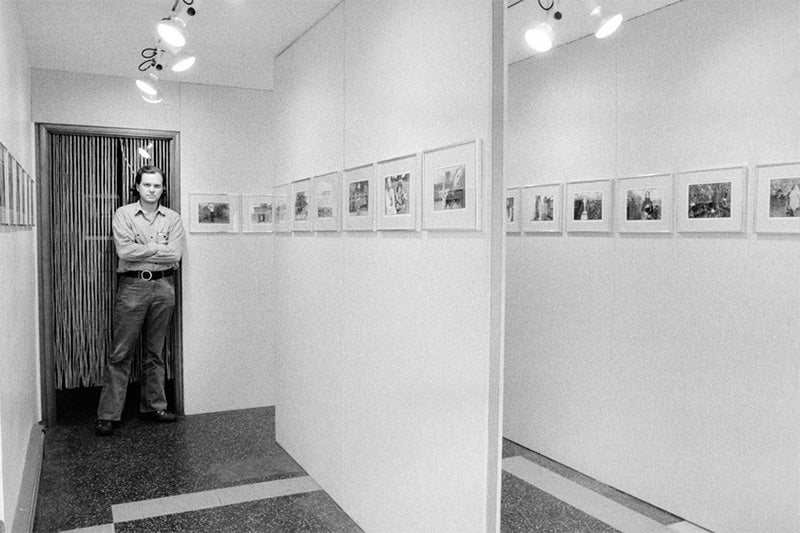

Above: Craig Hickman inside the original Lovejoy Street location of Blue Sky Gallery, circa 1975.

The Photo District News (PDN) notes in an October 28 Facebook post that “Community support and collective effort have contributed to the gallery’s longevity. For instance, Bruce Guenther, who recently announced his retirement as the chief curator of the Portland Art Museum, was instrumental in helping the gallery figure out how to buy the space they now occupy.” The purchase was made possible by “a large donation and support from the Portland arts community,” Hickman says.

Dolan notes that Portland is a magnet for creative endeavors, making it only natural for the art museum to stage a show about photography.

“I love the fact that photography gets part of the main stage at the museum, because this community adores photography,” she says. “It’s really important for us to celebrate this institution that has been part of the fabric of our arts community for forty years. The thing I’m most excited about is the range of style and composition and ideas. It’s really wonderful to see that many photographers in one space at one time.”

The accompanying full-color catalogue features essays by Dolan, the museum’s Minor White Curator of Photography, and Todd J. Tubutis, executive director of Blue Sky Gallery, as well as the interview with Blue Sky’s four surviving founders. Oregon Public Broadcasting also interviewed Hickman, Rauschenberg, and Dolan for a program that aired in October.

Dolan expects that the art museum show will prompt visitors to stop in at Blue Sky, too. “I hope our visitors after they see our exhibition … go over and see what photographs are being shown at Blue Sky [to] understand what they do from month to month as well.”

The Portland Art Museum is located at 1219 SW Park Avenue in Portland; hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday, Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday; 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Thursday and Friday.

Blue Sky Gallery is located at 122 NW 8th Avenue in Portland. Hours, as they’ve been for forty years, are still 12– 5 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday.

Above: Tom Champion, one of the early codirectors, hangs a show in Blue Sky Gallery.