At the time of the Iranian revolution, Taraneh Hemami was a Tehran-born college freshman who had moved to the United States after graduating high school. She studied art at the University of Oregon. She focused on studio work and wasn’t interested in politics.

Above: Taraneh Hemami poses in front of her work FREE, a temporary public art project at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. Photo by Tommy Lau.

During the fall of 1978 the Iranian Revolution was in full force. The citizens of Iran actively participated in countless rallies and protests of civil disobedience against the dictatorial Shah’s regime, the westernization of the culture, and exile of religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini.

Hemami focused on her studies at the UO with the hope of returning to Iran after graduation. She said it was “the most frustrating experience” being unable to be in Iran at this time, “witnessing the biggest event in my country through TV screens.”

“My parents were saying everybody was trying to leave,” Hemami said. “We were supposed to be the lucky ones.”

After earning her bachelor of fine arts degree in painting from the UO in 1981, Hemami didn’t realize that she would become inextricably involved in the political movement of that time through her art decades later.

Instead of moving back to Iran, Hemami moved to the Bay Area in 1982; she currently serves as adjunct instructor in interdisciplinary studies and diversity studies at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Her work has been exhibited at museums and galleries internationally, including Southern Exposure (San Francisco), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco), Rose Issa Projects (London), Victoria and Albert Museum (London).

In 2005, Hemami issued a call to collect the archives from the Iranian community in northern California. Her effort to assemble and curate those gathered works resulted in recovering an archive of original documents, banned books, and censored print material that belonged to the Iranian Student Association (ISA) in Berkeley, California. The archives traced political dissent in Iran from the early 1960s to the mid-1980s. Inspired by these archives, Hemami began creating personal projects with the materials and connecting with other artists also stirred by the archive to develop new works of their own.

In February 2015, Hemami returned to the UO for the first time since her graduation, to discuss what she’s learned in the intervening years about art and revolution, and the connective tissue that links them.

“For those of you who are ignoring what’s happening around you, beware,” Hemami told the gathering. “It may haunt you for the rest of your life.”

Above: Hemami’s Blood Curtain. Photo by Jay Jones.

Using media such as felt carpets, beaded curtains, assemblages of crushed glass, ceramic and lacquered sculptures, silkscreen fabrics, and aluminum glass, she said, “I carefully replicated logos, slogans, portraits, maps, newspaper headlines, creating monuments and memorials to historical events and people that were systematically erased in the official accounts of Iranian history.”

Her many productions include a large three-layered beaded curtain, Blood Curtain (2013), with 8mm faceted red beads that hung in an exhibition titled Resistance at Luggage Store gallery in San Francisco, California.

She has also invited other artists to participate in exploration of the archives in a series of projects titled Theory of Survival.

“Theory of Survival brings the underground culture of protest to the surface to investigate the connections between radical movements across times and geographies to the examination of a specific Iranian experience,” Hemami says.

The name Theory of Survival comes from the book The Refutation of the Theory of Survival, a publication from the ISA archives.

“Its altered title clicked with me,” she said. “These objects had survived the hands of censorship, crossing borders, dictatorships, and didactic ideologies. In a way, they represented us as immigrants in this country—and what we face on a daily basis. It’s not the ‘refutation’ of the theories they represented, so much as inquiries into and actual strategies of survival.”

In 2008, Hemami invited former ISA members to help organize the archival collection, which included pamphlets, posters, periodicals, postcards, and propaganda, for an acquisition proposal for the Library of Congress. The documents also included ISA’s published journals and newsletters that reflected the political sensibilities of the organization, which was active from 1964 to 1984.

The materials survived water damage, neglect, and a fire, and were archived after extensive researching, translating, scanning, and cataloguing. The Library of Congress acquired a portion of the archives in 2009, and the Hoover Institute at Stanford also owns some of the collection today.

Fabrications—the newest iteration of Theory of Survival—transforms the exhibition space in which it’s presented into a pop-up bazaar, or outdoor marketplace, with several booths and various installations by a collection of artists. At its initial exhibition in fall 2014 at Southern Exposure gallery in San Francisco, twelve artists were commissioned and a number of others participated in events and performances.

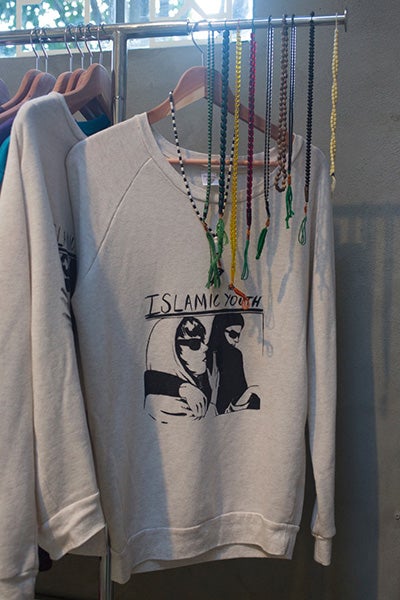

Taravet Telepasand, a Portland-based artist, created a series of T-shirts for her booth “Islamic Youth” as part of Fabrications.

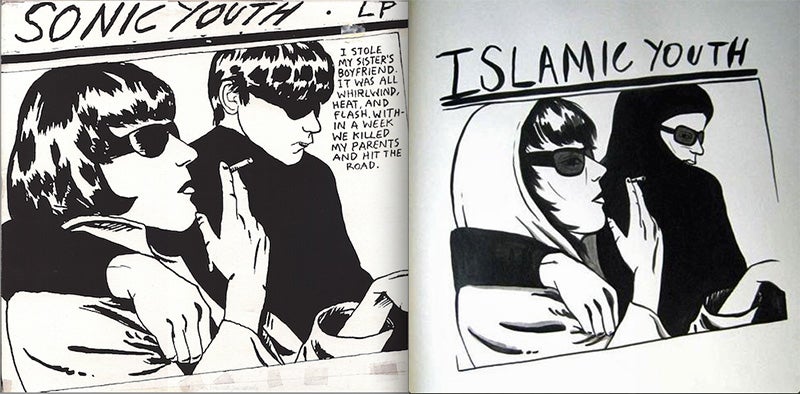

Above: Sonic Youth’s Goo album cover and Taravet Telepasand's Islamic Youth artwork side by side.

The project takes the iconic cover of the 1990 Sonic Youth album Goo, a black-and-white illustration of a man and woman, but places them in chadors, a scarf worn around the head and torso by Muslim women that only exposes the face.

This project was directly inspired by a personal story of smuggling Sonic Youth and other punk rock albums to Iran to Telepasand’s cousins in Iran in the 1980s when a ban on Western music made it difficult to access alternative music.

Music was a common element in several works of Theory of Survival, including in artist Morhshin Alayari’s #AsYouScrollDown, a work that turns hundreds of Twitter feeds into record albums. Patrons are invited to play the records and listen to the narratives of a revolution in the making. Popular photos from the 2009-2010 protests in Iran that were shared on social media were printed as vinyl cover art.

Amir H. Fallah’s booth “Failure” blended the influential culture of the 1960s and 1970s Bay Area counter-culture movement with the garment that symbolizes the Islamic Republic of Iran—the chador. Fallah used acid to bleach the chadors, which altered their colors, and burnt them, which produced holes in the fabric and stark patterns that stained the clot—a symbolic antithesis of the counter-culture movement’s colorful tie-dye. A mirror was included in the installation, and patrons were encouraged to wear them and take photos of themselves.

Hale Niazmand, a teen-ager during the revolution, created “2Die4,” a boutique of high-end clothing and accessories. This included jewelry resembling skin and bullet wounds. This object was one of the most popular items sold at the exhibition.

“I was just surprised, to tell you the truth. I had a hard time looking at it. It was basically a round bullet hole that you would wear around your neck,” Hemami said.

Above left: Hemami’s Theory of Survival has helped her retroactively understand her country’s history and to learn about the politics in play during the revolution. She said she was too young as a college freshman to understand the magnitude of the political upheaval happening at home. Photo by Catherine McElhone. Above right: Theory of Survival “brings the underground culture of protest to the surface to investigate the connections between radical movements across times and geographies to the examination of a specific Iranian experience,” Hemami says. Photo by Catherine McElhone.

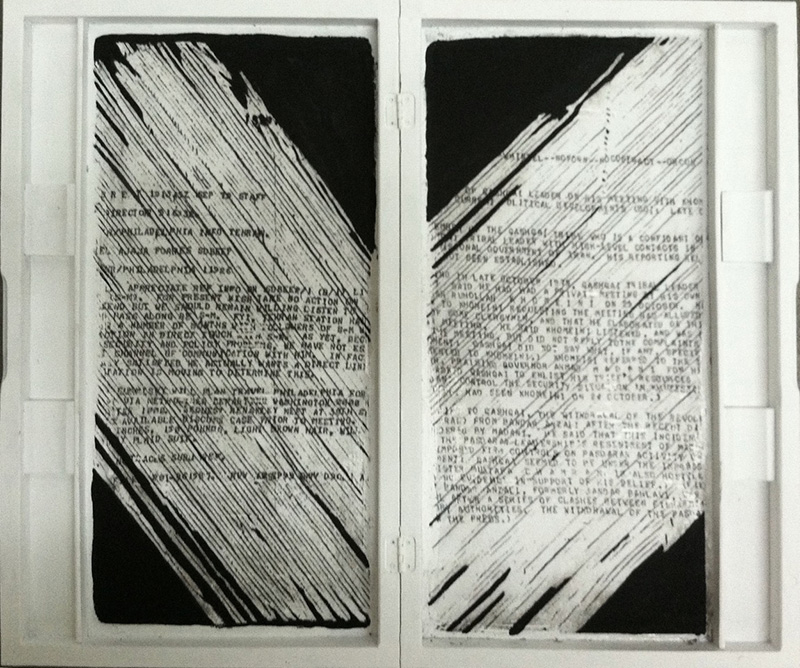

Above: Backgammon board, by artist Gelare Khoshgozaran, using stripped documents, as featured in Hemami’s Theory of Survival. Image courtesy Taraneh Hemami.

Gelare Khoshgozaran’s reponse to the pop-up bazaar was a backgammon set (“What’s a bazaar without a backgammon table?” she asked Hemami). Khoshgozaran recreated the open face of a backgammon board using the shredded pages of documents from the takeover of the American Embassy in Tehran, the material evidence for the Iran-Contra affair.

Typically, the game’s opposing pieces are black and white. However, in Khoshgozaran’s set, the pieces are covered in various patterns from the original document, which makes it impossible to differentiate the two sides, and the game becomes increasingly difficult as it progresses.

“It was hard to keep track. In this case, they were matching one another. It would get completely confounding and challenging to identify the two players who were supposed to be competing,” Hemami said.

Hemami also created a “souvenir shop” within the bazaar, in which powerful graphic imagery from the archives were offered as one-of-a-kind handcrafted or manufactured everyday objects, from tote bags and key chains to magnets and memorial china plates.

Hemami’s Theory of Survival has helped her retroactively understand her country’s history and to learn about the politics in play during the revolution. She said she was too young as a college freshman to understand the magnitude of the political upheaval happening at home. The project, she said, serves to generate conversation about the times and issues still faced today.

“Nobody talks about that era anymore. Its history is filled with misunderstanding and misinformation. It’s at the center of conflict between different generations,” she says. “There’s no place for dialogue. The whole project is imagined as a place to entice you to come closer and get involved, and maybe look at the history and how it connects to today’s unrest in that part of the world.”

Theory of Survival was endorsed by a Creative Capital grant, the Center for Cultural Innovation’s Artistic Innovation Award, the Creative Work Fund, and the San Francisco Arts Commission Cultural Equity grant. It has been exhibited in galleries around the world, including Southern Exposure (San Francisco), Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco), Rose Issa Projects (London), Victoria and Albert Museum (London).

Above left: Artist Amir H. Fallah’s bleach-stained chadors, as featured in Theory of Survival. Above right: The sweater featuring Taravet Telepasand’s repurposed image of the 1990 Sonic Youth album.